February 9, 2026

2 min read

Add Us On GoogleAdd SciAm

Mathematicians issue a major challenge to AI: show us your work

Frustrated by AI industry claims of proving math results without transparency, a team of leading academics has proposed a better way

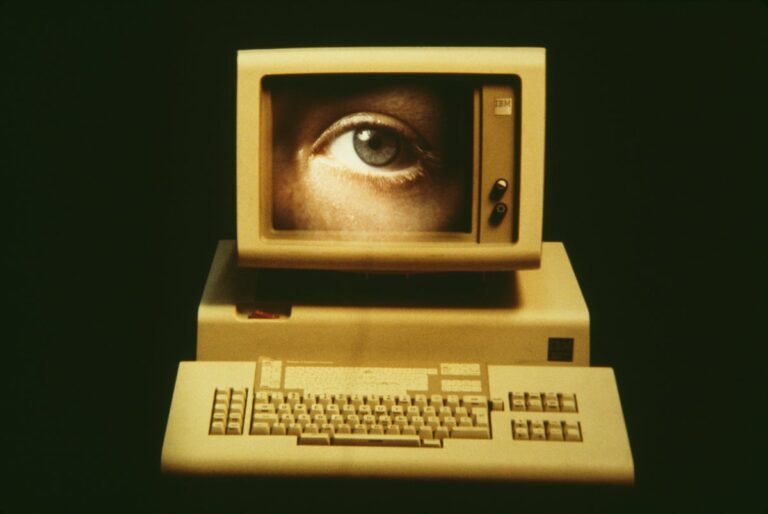

Alfred Gescheidt/Getty Images

The race is on to develop an artificial intelligence that can do pure mathematics, and a team of top mathematicians just threw down the gauntlet: an exam of actual, unsolved problems relevant to their research. They’re giving the AI’s a week to solve them.

The effort, called First Proof, is detailed in a preprint posted last Thursday.

“These are brand new problems that cannot be found in any LLM’s training data,” says Andrew Sutherland, a mathematician at MIT who was not involved with the new exam. “This seems like a much better experiment than any I have seen to date,” he adds, referring to the difficulty in testing how well AIs can do math.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The AI industry has become fixated on pure mathematics. Because mathematical proofs follow a checkable sequence of logical steps, the conclusion is true or false beyond any subjective measure. And that may offer a better way to compare large language models’ prowess than how convincing their poetry is. Startups dedicated to AI for mathematics have recently recruited a number of high-profile mathematicians.

These efforts have had some early successes: In 2025, Google achieved a gold-level score on the International Math Olympiad, an exam for prodigious high schoolers. And in the past few months, an AI has solved multiple “Erdös problems”—a trove of challenges set by the late mathematician Paul Erdös. Startup AxiomMath made headlines last week for successfully tackling several research-level (though far from groundbreaking) math questions.

But none of these are controlled experiments. Olympiad problems aren’t research questions. And LLMs seem to have a tendency to find existing, forgotten proofs deep in the mathematical literature and present them as original. One of AxiomMath’s recent proofs, for example, turned out to be a misrepresented literature search.

And some math results coming from tech companies have raised eyebrows among academics for other reasons, says Daniel Spielman, a professor at Yale University and one of the experts behind the new challenge. “Almost all of the papers you see about people using LLMs are written by people at the companies that are producing the LLMs,” says Spielman. “It comes across as a bit of an advertisement.”

First Proof is an attempt to clear the smoke. To set the exam, eleven mathematical luminaries—including one Fields medal winner—contributed math problems that had arisen in their research. They also uploaded proofs of the solutions, but have encrypted them. The answers will decrypt on Friday, Feb. 13, just before midnight.

None of the proofs are earth-shattering. They’re “lemmas,” a word mathematicians use to describe the myriad tiny theorems they prove on the path to a more significant result. Lemmas aren’t typically published as standalone papers.

But if AI can solve them, it would demonstrate what many mathematicians see as its near-term potential: a helpful tool to speed up the more tedious parts of math research.

“I think the greatest impact AI is going to have this year on mathematics is not by solving big open problems, but through its penetration into the day-to-day lives of working mathematicians, which mostly has not happened yet,” says Sutherland. “This may be the year when a lot more people start paying attention.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.