September 3, 2025

4 min read

What’s the Smallest Particle in the Universe?

The answer to this supposedly simple particle physics question isn’t so simple

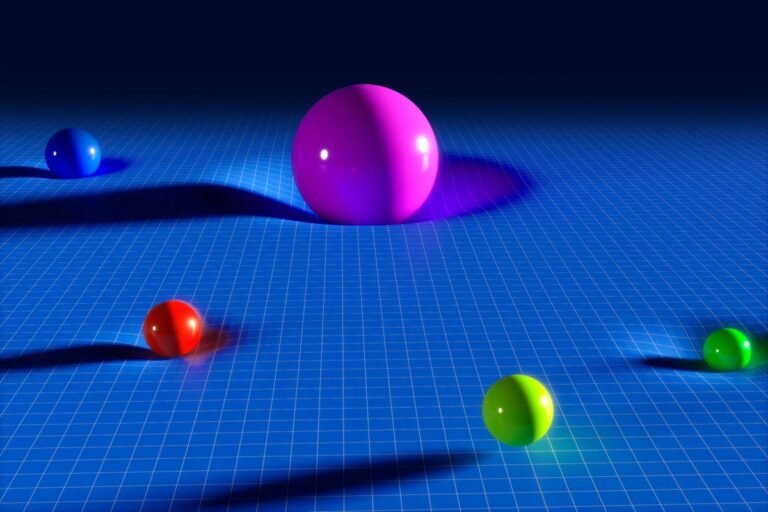

An artist’s concept of multiple types of subatomic particles.

Mark Garlick/Science Photo Library

Forget about turtles; for all practical purposes, it’s really particles all the way down.

Whether as the protons and neutrons that help form chemical elements, the photons that we perceive as light or even the flows of electrons that power our smartphones, subatomic particles constitute essentially everything any of us will ever experience. Ironically, however, because they’re so minuscule, the particles underpinning our everyday reality tend to escape our notice—and our comprehension.

Consider the seemingly simple matter of their size, the very thing that makes them so alien. We’re typically taught to imagine any and all particles as tiny, colorful spheres, as if they were solid things that we could lay a ruler alongside to determine their dimensions like we’d do for any other physical object in the world. But subatomic particles don’t actually look like that at all. And while, for the largest particles, there are ways to measure “size” in a very general sense, for those that are smaller and ostensibly more “fundamental,” the concept of size itself is so slippery that it becomes almost meaningless.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Still, if Google queries are any guide, people really do want to know “What’s the smallest particle in the universe?” Never mind that the better question might be “Is there any point in asking?”

First Things First

“There’s a lot of meanings for ‘small,’” says Janet Conrad, a particle physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Like, I could say a cotton ball is ‘small’ because it’s very light. Or I could say a tiny metal ball is ‘small’ because its radius is very small, but it would weigh a lot more than the cotton ball.”

Conrad’s point is that there’s a categorical difference between a particle that’s “smallest” in mass and a particle that’s “smallest” in diameter. There’s another important categorical difference to account for as well, a functional distinction between two different classes of particles: fermions, or “matter” particles such as protons or electrons that comprise everything in the universe, and bosons, or “carrier” particles such as photons that deliver forces between fermions.

And most fundamentally, there is the matter of so-called fundamental particles, which are set apart from seemingly nonfundamental ones. Whether it’s a fermion or a boson, physicists consider a particle “fundamental” if it cannot be broken down any further with any currently available technology. In that sense, some relatively well-known particles, such as protons, are not fundamental particles; if you hit a proton with a certain amount of force, it’ll burst into quarks, which are considered to be fundamental.

So in terms of physical size, you’d probably think that fundamental particles would be “smaller” than nonfundamental ones. But that’s where things get really tricky, says Juan Pedro Ochoa-Ricoux, a particle physicist at the University of California, Irvine. According to the Standard Model of particle physics, which incorporates all known particles and forces besides gravity to make ludicrously accurate physical predictions, all fundamental particles have no size whatsoever. That is, asking whether one is bigger or smaller than another is a nonsensical question, akin to wondering what’s north of “up” or trying to divide by zero.

Sizing Up Randomness?

“[Fundamental particles] are Euclidean points,” Ochoa-Ricoux explains. “They’re not even one-dimensional. We think of them as [zero-dimensional] points [that] don’t have a determined position. And so, rather than thinking of electrons as little balls going around an atomic nucleus, in reality, we should think of them as a cloud [of probabilities].”

All fundamental particles seem to be this way, showing no signs of deeper internal structure, Conrad adds. “We keep testing to see if there’s any spatial extent associated with them,” she says, “but we don’t see any evidence that there’s something inside of these particles.”

Physicists like to circumvent this uncertainty, Ochoa-Ricoux says, by doing some reverse calculations using Albert Einstein’s famous equation E = mc2, which quantifies the equivalence between energy and mass. Specifically, such calculations usually involve the electron volt (eV), a unit of energy for which 1 eV represents the charge of one electron. Using Einstein’s equation to convert this value to mass reveals that the electron effectively weighs about 0.51 mega-electron-volts per speed of light squared (0.51 MeV/c2)—that is, about 9.109 × 10–31 kilogram. In comparison, the “lightest” quark, the up quark, is more than four times heavier, weighing in at about 2.14 MeV/c2.

As small as these values are, they’re still much bigger than “zero,” which is the mass inferred for certain other particles. These so-called massless particles are arguably the best candidates for the “smallest,” too.

One Question, Many Answers

Strictly speaking of bosons, or force-carrying particles, the clear winner of the competition for “universe’s smallest particle” would be the massless photon. (Gluons—bosons that bind together quarks—are also thought to be massless but are much harder to study because they’re typically trapped inside protons and neutrons.) If we’re talking about fermions, the particles that are the building blocks of matter—a reasonable guess for the universe’s smallest particle would be the neutrino. This is a “guess” because we don’t really know the exact mass of a neutrino for certain, although we’re sure it’s not zero. To put the neutrino’s mass into perspective, it probably weighs about 0.45 eV/c2—less than one millionth the mass of an electron!

But again, as Ochoa-Ricoux and Conrad each independently emphasize, this is just one approach experts tend to use when considering a particle’s size. As with many kinds of scientific inquiry, the answer you get intimately depends on how exactly you’re asking the question.