February 16, 2026

2 min read

Add Us On GoogleAdd SciAm

Astronomers spot one of the largest spinning structures in the universe

This enormous chain of hundreds of galaxies—a cosmic filament—is twisting through space 400 million light-years away

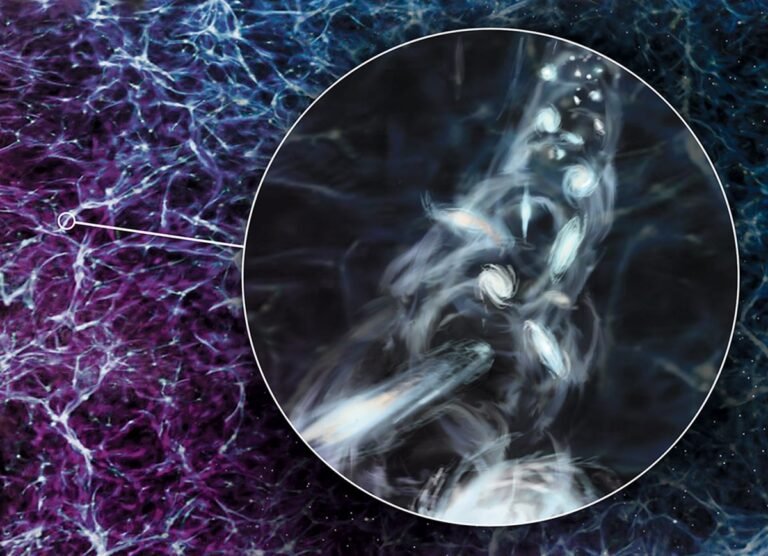

Artist’s interpretation of the newfound spinning filament.

The first time that University of Oxford astronomer Lyla Jung saw the cosmic configuration on her monitor, she almost didn’t believe it was real. But it was—and Jung and her colleagues went on to identify one of the largest rotating structures ever found in space: a chain of galaxies embedded in a spinning cosmic filament 400 million light-years from Earth.

The finding, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, may give astronomers new insights into galaxies’ formation, evolution and diversity, Jung says.

Galaxies are not positioned either randomly or uniformly in the universe; instead they are connected in structures called filaments that link them, together with dark matter, across space. Along with voids—empty spaces that contain very little matter—and groups of hundreds of thousands of galaxies known as clusters, filaments form what astronomers call the cosmic web.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

These filaments are the main channels through which matter flows, feeding galaxies and clusters as structures expand. “By studying filaments, we gain insight into how large-scale structure forms and how galaxies acquire their spins,” says astrophysicist Peng Wang of the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, who was not involved in the new study.

In 2021 Wang and his colleagues reported that based on calculations and satellite imagery, several filaments seemed to be rotating. The new study takes a closer look at one of these structures. Using data from the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa, which was helping to map cold hydrogen gas in nearby galaxies, Jung’s team found 14 hydrogen-rich galaxies arranged in a thin, 5.5-million-light-year-long structure. That structure was embedded within a filament 50 million light-years long that contains more than 280 galaxies.

The researchers observed that many of the individual galaxies MeerKAT detected were spinning—and, to their surprise, they also found that the entire filament, including the rest of its galaxies, appeared to be rotating in sync with that spin at a speed of about 110 kilometers per second, something astronomers hadn’t seen before. “I started doubting if it was real or if I did something wrong in the analysis,” Jung says.

Detecting this phenomenon “is exceptional,” Wang adds, because the observation signal is faint, and overlapping objects along the line of sight can muddy the picture without very careful data collection and modeling.

In later analyses, Jung and her team found that the filament is probably still taking on more material. Many of its galaxies seem to be in the early stages of growth, she says, because they appear rich in the hydrogen that provides fuel for new stars.

One of the most convincing pieces of evidence for the existence of dark matter comes from measurements of galaxies’ rotation. Studying the rotation of filaments could also reveal how much dark matter is in them, says astronomer Noam Libeskind of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam in Germany, who was not involved in the study. By revealing what portion of the universe exists in these filaments, Libeskind says, this study and future ones like it offer “a way of measuring the dark matter content of the universe.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.