Surveys are a cornerstone of social-science research. Over the past two decades, online recruitment platforms — such as Amazon Mechanical Turk, Prolific, Cloud Research’s Prime Panels and Cint’s Lucid — have become essential tools for helping researchers to reach large numbers of survey participants quickly and cheaply.

There have long been concerns, however, about inauthentic participation1. Some survey takers rush the task simply to make money. Because they are often paid a fixed amount based on the estimated time taken to complete the survey (typically US$6–12 per hour), the faster they complete the task, the more money they can make.

Studies suggest that between 30% and 90% of responses to social-science surveys can be inauthentic or fraudulent2,3. This problem is exacerbated in studies targeting specialized populations or marginalized communities because the intended participants are harder to reach and are often recruited online, raising the risk of fraud and interference by automated programs called bots4,5. Those percentages are much higher than the amount of fraudulent responses most studies can cope with, if they are to produce results that are statistically valid: even 3–7% of polluted data can distort results, rendering interpretations inaccurate6. And the problem is getting worse.

AI chatbots are infiltrating social-science surveys — and getting better at avoiding detection

A parallel industry has emerged offering scripts, bots and tutorials that (legitimately) make it easy to partially or fully automate form filling (see, for example, go.nature.com/4q8kftd). The use of artificial intelligence for crafting responses is on the rise, too. For instance, answers mediated by large language models (LLMs) accounted for up to 45% of submissions in one 2025 study7. The advent of AI agents that can autonomously interact with websites is set to escalate the problem, because such agents make the production of authentic-looking survey responses trivially easy, even for people without coding experience.

Researchers and survey providers have long developed tools to prevent, deter or detect inauthentic survey responses. CAPTCHA8, for example, tests whether a user is human by requiring them to identify distorted text, sounds or images. Such methods could confuse unsophisticated bots (and inattentive humans), but not AI agents.

A few detection measures can distinguish agent-generated responses from genuine ones by exploiting the way LLMs rely on training data to produce responses and their lack of ability to reason contextually9. For example, LLMs might label an image of a distorted grid or colour-contrast pattern as an optical illusion even after the illusion-inducing elements have been digitally removed, relying on learned associations rather than perception7,10. Humans, by contrast, respond to what they actually see, creating a detectable difference between human and AI interpretations. However, these distinctions are likely to fade as AI advances, rendering such tests unreliable in the near future.

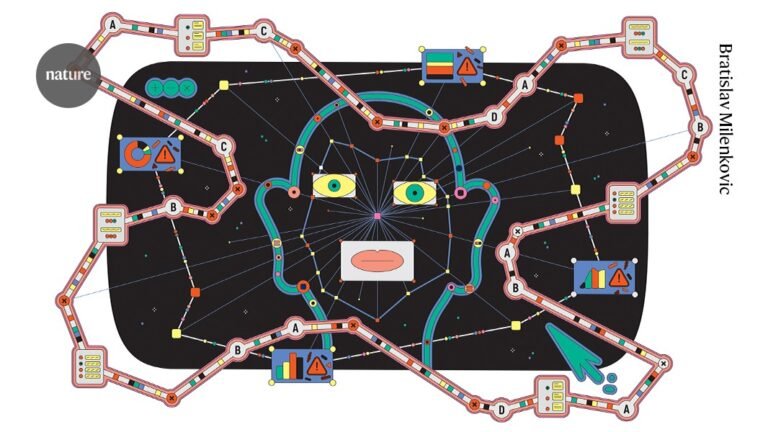

AI-agent detection has been described as a continual game of cat and mouse, in which “the mouse never sleeps”11. Here, we lay out four steps to minimize the risk of survey pollution by AI agents. Using a combination of these detection strategies will probably be necessary to enable researchers to continue to separate out authentic responses from AI bots (see ‘Outwitting AI agents’).

Look for response patterns

One approach is to assign probabilistic scores to survey submissions by comparing each response to known patterns in human and AI-generated answers12. LLMs tend to produce answers that have lower variability. For example, when asked to describe their political views by expressing their level of agreement on a series of statements, humans tend to use the extremes of the scale more often than bots do. When sufficient text is available, open-ended responses can also reveal linguistic patterns13,14.

Detection tools can exploit such distinctions. By comparing individuals’ responses with sample replies to the same questions answered by genuine humans and by AI, tools can flag responses in which patterns closely match the latter. The potential of such an ‘AI or human’ filter is buttressed by recent findings that LLMs continue to struggle to accurately simulate human psychology and behaviour15.

Although promising, this method has one crucial limitation: it cannot reliably identify individual responses as bot-generated (because the detection method is probabilistic, not deterministic), making it extremely difficult to flag a single survey entry with certainty.

Track paradata

Paradata refers to the information that describes how survey responses were generated, such as the number of keystrokes a respondent used, the use of copy–paste functionality or the time spent answering a given question. It is relatively straightforward to embed basic keystroke tracking into a survey (although appropriate ethical considerations such as consent and justified use should be taken into account).

AI chatbots are already biasing research — we must establish guidelines for their use now

Tracking paradata can help to identify likely inauthentic responses by highlighting inconsistencies. For instance, if leaving a 100-word open-text response took 5 seconds, it is likely that the response was at least low effort or potentially AI-generated. Furthermore, if that response appeared in the survey window all at once (instead of gradually, stroke-by-stroke), this provides evidence that the response was generated outside of the survey environment — say, in another browser window16. Some survey companies have developed their own tools to flag open-text responses that are suspected to be inauthentic in such ways.

However, this approach is not always appropriate, because some survey tasks might require access to external information. Another problem is that this might not work as well for survey questions that don’t require text input, although suspicious click and mouse-movement patterns can still help to identify low-quality data. Importantly, newer LLMs and some AI browser agents are already capable of creating realistic paradata6,17.

Find vetted survey populations

Researchers can rely on recruitment platforms that draw participants from census-based, probability-sampled pools. For example, panels in the Netherlands and France recruit households using official population registers maintained by national statistics agencies. Although this does not prevent participants from using AI to complete surveys, it ensures that responses come from real individuals, and typically only one per household.

Social-science research relies on gathering online survey data for experiments.Credit: Milky Way/Getty

Collaborating with such panels can enhance data integrity. However, these panels are generally more expensive to use than typical online platforms because enrolment involves strict verification of identities and/or census-based selection, and the participant pool is regularly vetted. Furthermore, data collection occurs only a few times per year, often combining multiple surveys, which requires careful timing and limits the number of questions that can be included in any single study.

For survey platforms, there are several potential pathways forwards as they try to adapt to AI. Platforms might consider capping the number of allowed submissions per day from a user; combined with identity verification, this could prove to be an effective deterrent for inauthentic submissions. Platforms could also enforce a reputation or sanctions system to incentivize user authenticity.