As Caitlin MacLeod-Bluver drove to her teaching job at Winooski High School in the small refugee resettlement city outside of Burlington, Vt., on Jan. 12, she listened to news related to the shooting death of Minnesota resident Renee Good by an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent days earlier. And she wondered how her friend Tracy Byrd and his students were faring.

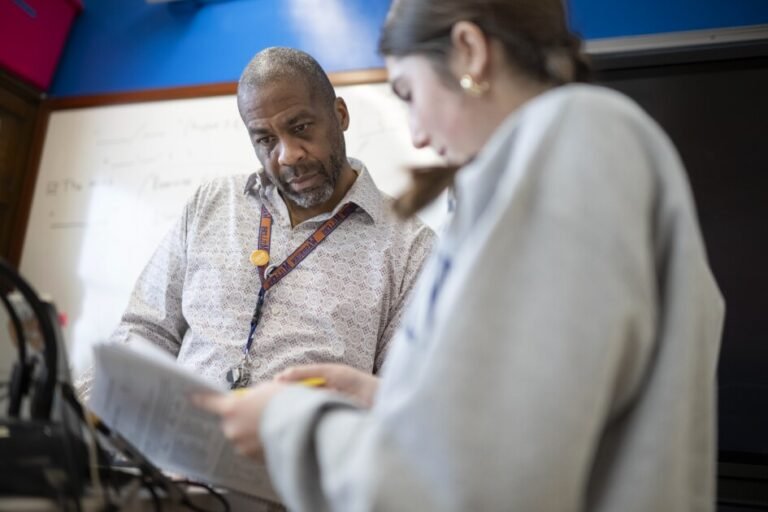

Byrd, like MacLeod-Bluver, is a member of the 2025 State Teachers of the Year cohort, sponsored by the Council of Chief State School Officers. Also like MacLeod-Bluver, he’s a high school English teacher. And, despite living about 1,200 miles from one another, they both know what it’s like to worry about students who are afraid to come to school. Byrd teaches at Minneapolis’ Washburn High School, a mile-and-a-half from where Good was killed.

“He was on my mind,” said MacLeod-Bluver.

That morning, MacLeod-Bluver sent Byrd a text to let him know she was thinking about him and his students. She then began her American literature class the way she always does—by reading a poem. That day, she chose Amanda Gorman’s poem, “For Renee Good.”

She also told her class about her friend, Byrd, and what his students were going through; his district had started offering online learning options, as many immigrant students and their families feared coming to school.

“That really moved kids,” said MacLeod-Bluver. “These concerns are not unfamiliar to them.”

About 9% of Winooski district’s students are Somali. The district had experienced an onslaught of hateful attacks in December after it displayed a Somali flag on one of its buildings as a show of solidarity for community members, Winooski Superintendent Wilmer Chavarria told Education Week. So when MacLeod-Bluver suggested to students that they participate in a video voicing their support for Byrd and his students, they immediately agreed.

“A lot of them just wanted to say a quick word about lending their support and solidarity to Tracy’s students,” she said.

“No kid, no student, should be going through this,” one student said. Another said, “Just letting you know that you’ve got our support.”

Byrd initially watched the video alone, admitting that it brought him to tears. He then shared it with his students and his principal; it eventually aired on the district’s YouTube channel.

“This is how good people are,” Byrd said, of the gesture. “People are cheering for you all of the time, and sometimes you don’t even know it, but they’re cheering for you.”

Teaching can be lonely without peer networks

It’s normal for teachers to worry about their students, even more so in challenging times. And with little opportunity during the school day to connect with colleagues, teachers often worry alone. This can lead to or exacerbate feelings of loneliness, isolation, and burnout.

In recent years, particularly post-pandemic, experts have highlighted the urgent need for students to build healthy relationships. Less public attention, however, has been paid to teachers’ loneliness.

“Teachers still feel alone. We are regulating very dysregulated children and we’re dysregulated ourselves. We’ve got to understand and have real conversations about what is happening,” Kate Collins, a 1st grade teacher at Bluff Park Elementary in Hoover, Ala., and one of the finalists for the 2026 National Teacher of the Year award, told Education Week.

Finding time to have these conversations can be challenging. Teaching multiple classes a day, planning, grading, and taking on other work tasks typically leave little time for teachers to check in with one another—both during routine times and when crisis hits, putting student well-being is at stake.

But carving out the time is worthwhile. Lacking a strong peer network can make teachers more likely to want to quit their jobs, according to a 2023 Australian study that surveyed 426 teachers. Conversely, teachers who participated in the study cited positive relationships with colleagues as a key factor for wanting to stay.

Similarly, strong relationships with other teachers and supportive school leaders proved among the biggest contributors to educators’ positive well-being and mental health in the 2023 State of the American Teacher Survey by the RAND Corp.

Finding ways to create teacher connections

While collaboration among teachers at the same school can be valuable, some teachers find meaning in connecting with like-minded peers across the country.

For example, in a recent EdWeek opinion piece, New York City high school math teachers Bobson Wong and Larisa Bukalov shared how they’ve avoided burnout by connecting with communities of educators—outside of their school walls.

They’ve found support through a variety of sources, from local teacher organizations to social media platforms, which gives them access to teachers around the globe. Intentionally seeking out other educators has made them better teachers, they said.

“In short, connecting with other educators has made us less isolated and more energized, which in turn has kept us in the profession,” Wong and Bukalov wrote.

Byrd, the Minnesota teacher, maintains that he and other members of the 2025 state teacher of the year cohort, who became close through a yearlong professional development experience, will always remain tight. “We’re forever the TOY class of 2025,” he said. “We are connected through that.”

The cohort is invited to participate in regularly scheduled Zoom meetings, where members might go from discussing the grind of the second semester to sharing photos of new babies.

Then, of course, there are impromptu messages of support like the one that MacLeod-Bluver sent Byrd in the wake of Good’s killing in Minneapolis.

“So often, for me, it’s small conversations with like-minded teachers that push my [teaching] practice,” said MacLeod-Bluver. “That is really the best type of professional learning and one of the coolest things, especially in moments like this crisis.”