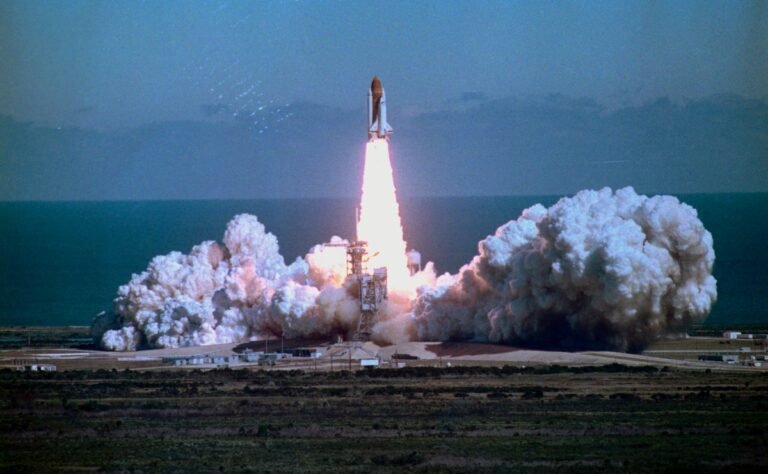

Forty years ago today, disaster struck NASA’s human spaceflight program when the space shuttle Challenger exploded 73 seconds after blastoff, killing all seven people onboard.

The tragedy nearly brought the shuttle program to an early end. Decades later, the mistakes that led to the Challenger disaster, as well as fallout from the similar 2003 loss of the shuttle Columbia, loom particularly large now, as NASA seeks to launch four astronauts on the ambitious Artemis II mission around the moon as early as next week.

The mission will be the first crewed flight of the massive Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion capsule, as well as the first time that humans have left Earth’s orbit since the final Apollo mission in 1972. Already NASA has faced public scrutiny over its handling of unexpected behavior from Orion’s heat shield—crucial equipment to protect astronauts as they return to Earth—during an uncrewed orbital test flight in 2022.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

NASA believes that changes made as a result of Challenger and other disasters in its history are enough to keep Artemis crews safe. “Challenger … brought out aspects of the agency which hopefully no longer exist and which we are always working toward addressing,” says Tracy Dillinger, safety culture program manager at NASA’s Office of Safety and Mission Assurance. “Space is risky. We know that, and our astronauts know that. We just want to be smart about the risks that we accept.” Currently, the Orion heat shield is widely believed to be the biggest risk to the crew; NASA has said the concern is addressed by changes to the Artemis II flight path.

From Routine to Disaster

The 1986 Challenger disaster occurred on the STS-51L mission, the 25th flight in NASA’s shuttle program, which was approaching its fifth anniversary. During the weeklong mission, crew had an eclectic agenda—observe Halley’s Comet and deploy both a communications satellite and an astronomical instrument into Earth orbit—but was most notable for one of its crew, Christa McAuliffe.

McAuliffe had taught middle and high school and was selected to fly after a nationwide “Teacher in Space” competition. She planned to teach two lessons from orbit, and her inclusion was part of a broader campaign by NASA to portray shuttle spaceflight as an ordinary, low-risk activity that nonastronauts could take part in.

“It’s sort of an all-purpose carryall vehicle often referred to by the astronauts themselves as a space truck,” says Jennifer Levasseur, a space historian and curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. “The space shuttle is intended to be very regular, it’s meant to be routine, it’s meant to be safe—so safe that the astronauts don’t even have to wear spacesuits.”

On that chilly late January morning, thanks to the excitement around McAuliffe’s flight, some 2.5 million students nationwide tuned in to watch the launch—only to see disaster unfold on live television. The so-called O-rings that joined the cylindrical segments of one of the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters failed under launch conditions far colder than they’d been designed for. Just more than a minute after ignition, the ruptured booster caused the shuttle’s giant external fuel tank to explode, tearing the vehicle to pieces over the ocean and dooming all seven astronauts.

Engineering Safety Culture

With the world watching, NASA scrambled to figure out what went wrong and how to fix it—all while wading into a deeper debate: Was human spaceflight still worth the risk of catastrophic loss? Although NASA rejected calls to end the space shuttle program, it paused flights for nearly three years as it pored over data from the Challenger disaster.

With diagrams, charts and dense technical writing—in a report that spanned more than 200 pages, not including its 15 appendices—NASA officials deconstructed the failure. That document highlighted not only the thermal constraints of the O-rings but also the design limitations inherent to the shuttle and the sociological pressures surrounding the program that put those O-rings in place and drove the launch forward.

“It was very apparent on multiple missions prior to STS-51L that there was an issue with the solid rocket booster sections and the way they joined together,” Levasseur says. Some safety concerns were even expressed before any shuttle ever flew. And on the morning of launch, when an engineer said he worried about the O-rings in the chilly weather, program managers who wanted the agency to successfully fly shuttles routinely decided to let the launch proceed anyway.

“Despite all of that knowledge, NASA was pressing ahead,” Levasseur says. “Its management said, ‘We have a schedule.’” That “launch fever” or “go fever,” as well as recurring O-ring anomalies that lulled managers into overlooking them, emerged as the true downfall of Challenger. Extreme cold made the O-rings fail, but NASA’s culture was just as blameworthy and needed a retrofit more urgently than any piece of shuttle hardware.

Smaller versions of NASA’s Challenger investigation play out today, says Sandra Magnus, a part-time professor of the practice of engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology and former NASA astronaut who previously served on NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel. “Whenever there’s a mishap, whether it’s something huge like Challenger or something a little bit less life-threatening, NASA has a process of going through, trying to understand what happened and why it happened,” she says.

NASA’s Artemis II rocket rolled to the launch pad on January 17, 2026, in anticipation of a launch next month.

The Ambitions of Artemis

Now NASA is facing its first crewed journey beyond Earth’s orbit since 1972, and many iterations of the agency’s safety investigations processes have occurred along the path to launch to protect four astronauts: NASA’s Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover and Christina Koch and the Canadian Space Agency’s Jeremy Hansen. They will be the first humans to launch on the SLS megarocket and its Orion capsule, and if all goes smoothly, they will set a record for humans reaching the farthest distance from Earth.

Some worry how they will fare during their return home, when their capsule must re-enter and traverse Earth’s thick atmosphere, enveloped for long, nail-biting minutes in a friction-kindled fireball. Orion is equipped with a heat shield, of course—one that combines updates based on knowledge from both Apollo and the space shuttle program, Levasseur notes.

Examining the Orion capsule that flew on the uncrewed Artemis I mission in 2022, NASA officials noticed that huge chunks of its heat shield had unexpectedly blown away. It’s an issue engineers have been investigating in the years since the test flight, and they say that adjusting Orion’s path toward Earth—plunging faster through the atmosphere at a steeper incline instead of a shallower, more prolonged descent—should safeguard against the problem.

But that’s not the same as redesigning the heat shield, and the agency opted not to test the heat shield on this new reentry profile before committing Artemis II’s astronauts to it. Redesigning the heat shield, NASA officials say, would have caused too much delay, and a new reentry test was deemed too expensive.

The Artemis I mission’s Orion heat shield seen after the 2022 uncrewed test flight.

An observer would be hard put to determine whether that choice reflects launch fever once again breaking through procedural norms. Artemis is a massive program—NASA estimated in 2024 that its costs since October 2011 would reach $93 billion by October 2025—and that can inherently bring pressure to keep things moving, says Jordan Bimm, a space historian at the University of Chicago.

And NASA has plenty of pressures to juggle. “NASA’s never been in a moment like this before,” Bimm says. Across the horizon of spaceflight, the agency is juggling negotiating multibillion-dollar contracts with commercial giants such as SpaceX and Blue Origin, while competing with relative newcomers to spaceflight, such as China and India, that are pursuing their own crewed ambitions.

The agency set what experts say was a promising example during the Artemis I mission, which was repeatedly delayed, including even rolling the massive rocket off the launch pad to shelter it from a hurricane.

For Levasseur, that suggests the people leading NASA today will make the hard choices that keep their crews safe. “They’re people who were children or young people during the 1980s, who were inspired by the early space shuttle flights,” she says. Many, like her, were shaped by watching the Challenger disaster as a child, or by the later Columbia tragedy. “Those memories are there, and they’re not going to want to make the same mistakes that were made before.”